Review the latest recommendations with

Sarah M. Temkin, MD, FACOG

Dr. Temkin is a gynecologic oncologist and equity advocate

Learning Objectives: Upon completion of this activity, participants should be better able to

- Understand the benefits and the risks of cervical cancer screening

- Become familiar with the clinical trials that led to the evidence for current cervical cancer screening guidelines and recommendations

- Compare the efficacy of different screening options, cytology, contesting, primary HPV testing for different age groups

- Consider the best frequency and type of screening for an individual patient and your practice population

CONTENTS:

Currently, women ages 30 to 65 have multiple options when it comes to cervical cancer screening. These options include (1) co-testing (cervical cytology and HPV testing), (2) cervical cytology only and (3) HPV only. How clear is the evidence behind these options?

BACKGROUND:

- Cervical cancer remains a major public health concern

- Globally: > 500,000 women per year affected | Fourth most common cause of cancer death among women worldwide (Arbyn et al. Lancet Global Health, 2020)

- US: Estimated 13,800 women will be diagnosed with cervical cancer in 2020 and more than 4,000 of women will die(Siegal et al. A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 2020)

- Human papillomavirus (HPV) causes most cervical cancers

- ≥70 percent of cervical cancer cases attributed to HPV-16 and HPV-18 | The remainder are caused by other high-risk HPV types (Munoz et al. NEJM, 2003)

- Sexual transmission is a nearly exclusive pathway of HPV transmission | HPV estimated to be most common sexually transmitted infection in the US | By age 50 approximately 80% of women have been infected with some type of HPV (Nielsen et al. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 2008)

- Most women who acquire the HPV virus do not develop cervical cancer

- 90% of HPV infections resolve on their own within 2 years | A small number of women do not clear the HPV virus and are considered to have a persistent infection (Munoz et al. NEJM, 2003)

- Cervical cancer is a preventable malignancy and worldwide eradication is a feasible goal

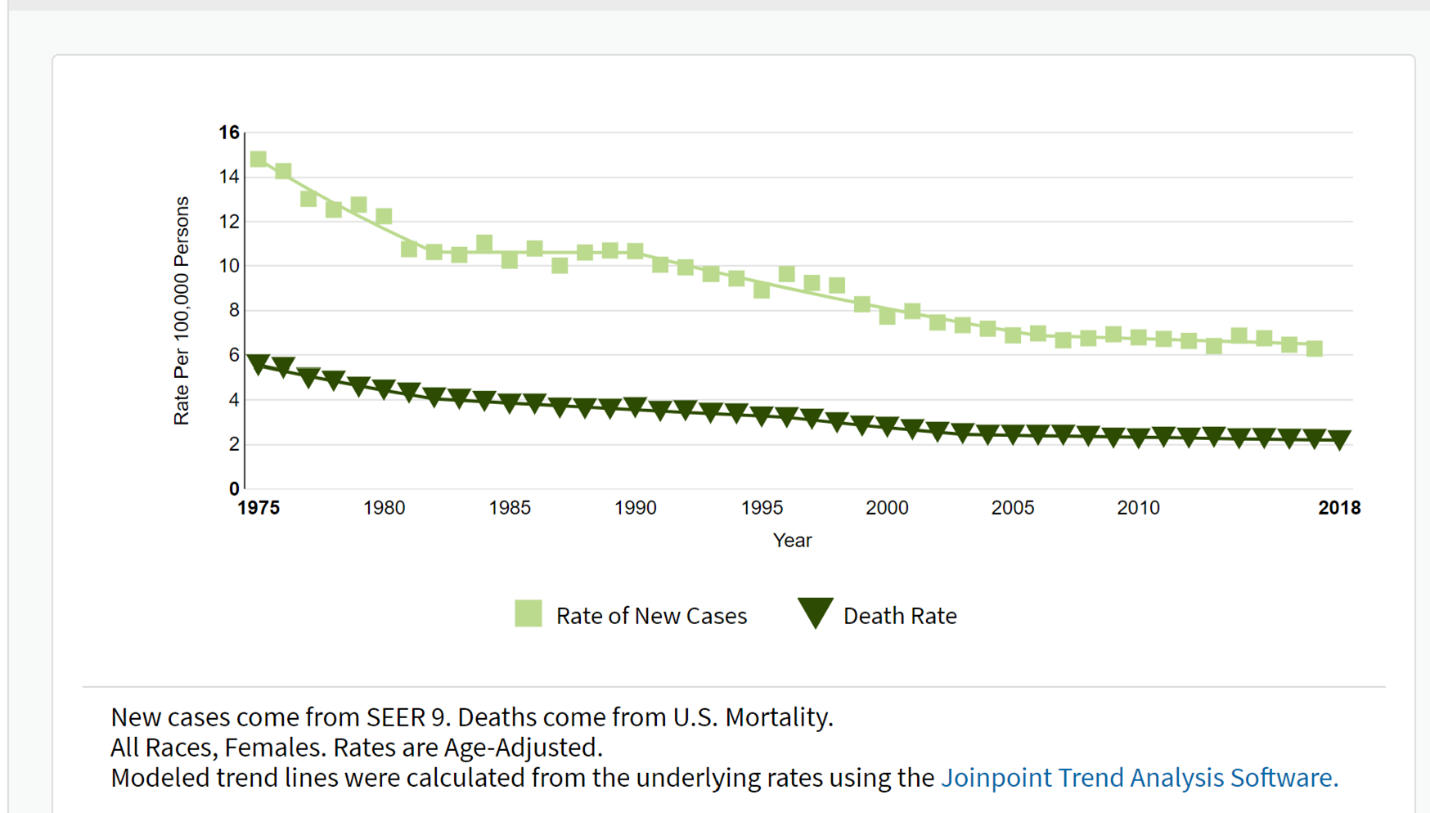

- Widespread adoption of pap smear screening in the US during the 1950’s and 60’s led to declines in incidence and mortality

- Overall incidence rates for invasive cervical cancer decreased by 54% over the 35 years from 1973 to 2007

Cervical Cancer: New Cases, Deaths and 5-Year Relative Survival (credit SEER)

Note: Most women who have abnormal cervical cell changes that progress to cervical cancer have never had a Pap test or have not had one in the previous three to five years

KEY CONCEPTS WHEN IT COMES TO SCREENING:

What are the Harms of Overscreening?

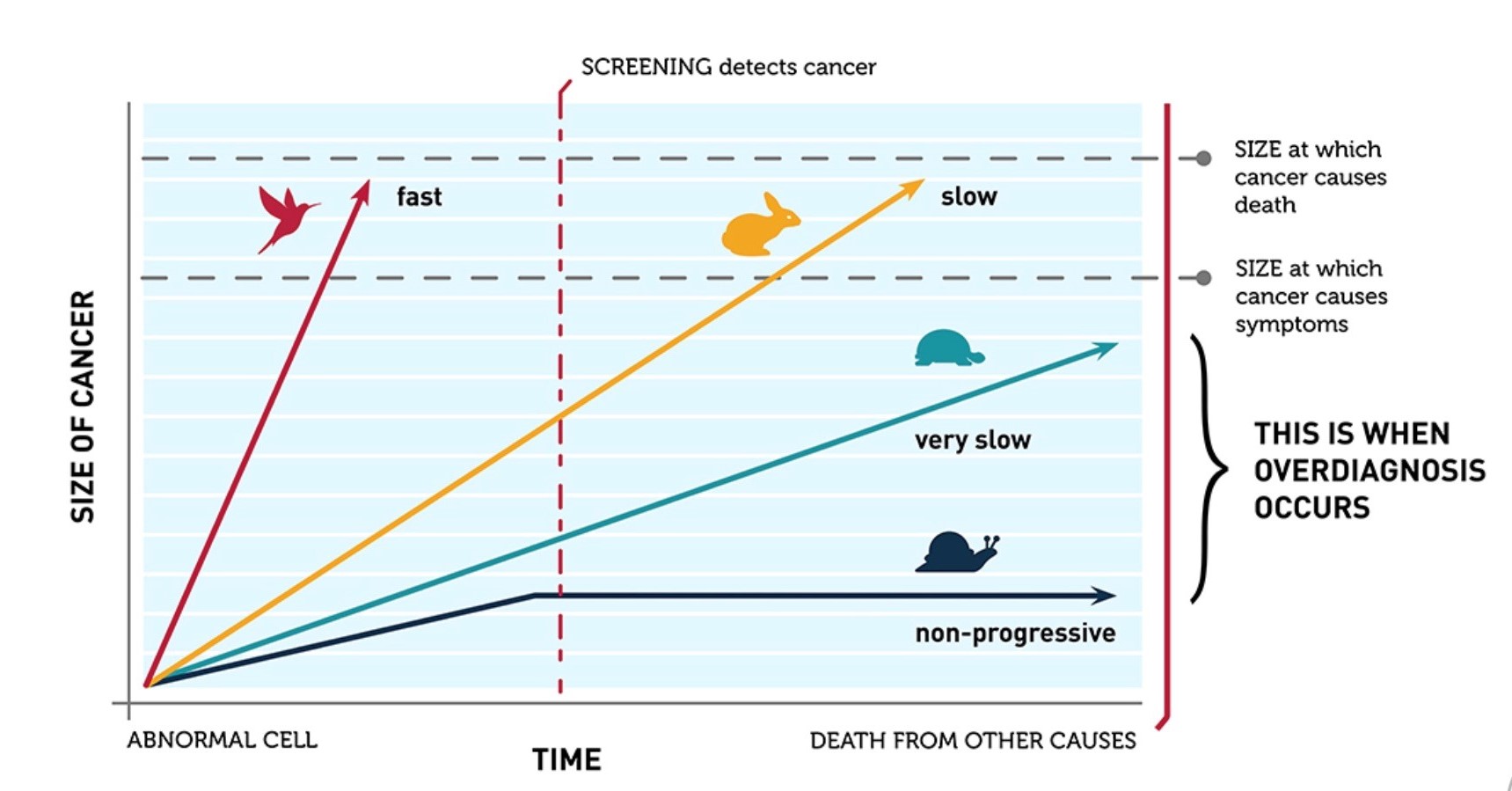

- Tumor biology drives the efficacy of screening for an individual disease (Esserman et al. Lancet Oncology, 2014)

- For very slow growing conditions or precancerous lesions that may regress without treatment such as cervical cancer, screening too frequently may lead to overdiagnosis – the diagnosis of a condition that would not have required treatment if it had not been diagnosed

- Screening has downstream consequences

- Cost | Time away from work and other activities | Occasional physical discomfort

- False positive screening results can lead to unnecessary follow-up tests (e.g., invasive biopsies, anxiety)

- Colposcopies, LEEPs and cone biopsies are uncomfortable

- Excisional biopsies in nulliparous patients may increase the risk of preterm delivery

Overdiagnosis: Size vs Time (credit NCI)

What are the Benefits Related to Cervical Cancer Screening?

- Cervical cancer is a preventable malignancy and worldwide eradication is a feasible goal

- Screening can alter the natural history

- Screening allows for detection and removal of high-grade precancer

- Allows for the early detection of invasive cervical cancer

- Widespread adoption of pap smear screening in the US during the 1950’s and 60’s led to significant declines in incidence and mortality

- Overall incidence rates for invasive cervical cancer decreased by 54% over the 35 years from 1973 to 2007

- Most women who have abnormal cervical cell changes that progress to cervical cancer have never had a Pap test or have not had one in the previous three to five years

KEY PUBLICATIONS:

HPV vs Cytology

Ronco et al. Lancet, 2014

- Combined results of 4 randomized trials in Europe (Sweden, Netherlands, England and Italy)

- Participants

- Women ages 20 to 64

- Study design

- Different protocols between studies

- Randomized to HPV-based or cytology-based screening

- Results

- 176,464 participants

- HPV-based screening provides 60-70% greater protection against invasive cervical carcinomas vs cytology

- Rate ratio of 0.60 (95% CI, 0.04-0.89) in favor of HPV testing for the detection of invasive carcinoma

Leinonen et al. BMJ, 2012

- Prospective randomized trial in Finland

- Participants

- Women ages 25 to 65

- Study design

- Participants followed over one screening round of five years

- HPV group (followed by cytology if positive): 101,678 women

- Primary cytology group: 101,747 women

- Participants followed over one screening round of five years

- Results

- Hazard ratio: 1.36 (95% CI, 1.09-1.59) for detection of CIN3/AIS for primary HPV screening

- Cumulative detection rate was 0.0057 (0.0045 to 0.0072) for HPV screening vs 0.0046 (0.0035 to 0.0059) for conventional screening

- “HPV screening could increase the overall detection rate of cervical precancerous lesions only slightly”

Ogilvie et al. JAMA, 2018

- Prospective randomized clinical trial in Canada

- Participants

- Women ages 25 to 65

- Study design

- Participants followed for (CIN) grade 3 or CIN3+ detected up to and including 48 months

- HPV group: 9552 women | Negative status returned in 48 months | Reflex cytology for positive HPV results

- Cytology group: 9457 women | Negative status returned in 24 months | If negative at 24 months, returned at 48 months | Followed by reflex HPV testing for women with ASCUS

- Participants followed for (CIN) grade 3 or CIN3+ detected up to and including 48 months

- Results

- The CIN3+ incidence rate (primary outcome)

- HPV group: 2.3/1000 (95% CI, 1.5-3.5)

- Cytology group: 5.5/1000 (95% CI, 4.2-7.2)

- CIN3+ risk ratio: 0.42 (95% CI, 0.25-0.69)

- For patients who were negative at baseline

- HPV-negative women, had a significantly lower cumulative incidence of CIN3+ at 48 months than cytology-negative women | CIN3+ risk ratio, 0.25 (95% CI, 0.13-0.48)

- “…by adding cytology to the intervention group, an additional 3 CIN2+ lesions were detected in HPV-negative women. In contrast, by adding HPV testing to the control group, HPV testing detected 25 CIN2+ lesions that would not have been detected by cytology alone”

- The CIN3+ incidence rate (primary outcome)

Sankaranarayanan et al. NEJM, 2009

- Prospective randomized trial in rural India

- Participants

- Women ages 30 to 59

- Low resource setting

- Randomized to 4 groups

- HPV group

- Cytology group

- Visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) group

- No screening (standard of care)

- Results

- There was a decrease in cervical cancer deaths among the HPV group vs standard care (no screening)

- Hazard ratio 0.52 (95% CI, 0.33 to 0.83)

- Reduction is deaths driven by ‘stage migration’ (a lower stage at diagnosis for women who developed cervical cancer)

- Cytologic screening or VIA did not lower the cervical cancer mortality rate

- There was a decrease in cervical cancer deaths among the HPV group vs standard care (no screening)

Relative Contributions of Cytology and HPV tests within Cotesting

Kaufman et al. AJCP, 2020

- There are no head-to-head studies that evaluate co-testing vs HPV only

- Kaufman et al. performed a review on a large commercial database (2010 to 2018)

- 13,633,071 women ≥30 years | Diverse population in the US

- 18,832,014 cotest results

- Goal of the study: To evaluate the results of liquid-based cytology and HPV testing in cotesting preceding cervical cancer and precancer diagnoses

- Results

- 1,615 cotests preceded 1,259 cervical cancer diagnoses | 11,164 cotests preceded 8,048 cervical precancer diagnoses

- More women subsequently diagnosed with cervical cancer within 1 year of cotesting were identified by cytology result (P<.0001)

- Cytology: 85.1%

- HPV: 77.5%

- More women subsequently diagnosed with CIN3/AIS within 1 year of cotesting were identified by HPV result (P<.0001)

- Cytology: 89.3%

- HPV: 97.6% was more frequently positive than LBC prior

- False-negative rate in women with cervical cancer

- Positive cytology/negative HPV: 13.1%

- Rate increases if testing >12 months

- The authors conclude

…Liquid-based cytology (LBC)/human papillomavirus (HPV) cotesting enhances screening for detection of cervical cancer in women 30 years an older, more so than LBC or HPV alone among women receiving cotesting

…detection of prevalent “precancers” (detection sensitivity) is likely to overestimate the effectiveness of any screening formulation in preventing invasive cancer

Because of this bias, the performance of screening tests targeting the diagnosis of invasive cancer as the primary end point of screening effectiveness is especially relevant

THE WRAP UP:

Evaluating the Studies

- HPV‐based cervical cancer screening has superior sensitivity and long‐term negative predictive value compared with cytology‐alone screening demonstrated in several randomized controlled trials

- However, there are no direct randomized head-to-head studies between HPV only vs co-testing

- Large retrospective database studies of a heterogeneous population that compared HPV to co-testing suggest that HPV only may be better at detecting precancerous lesions but including cytology leads to better detection of cancers within the subsequent year

- Data from randomized controlled trials that assessed HPV only strategies may not be representative of the US population

- Adherence to follow-up in the real world may be quite different

- Few participants from under-represented minority populations with higher disease burden (Black and Hispanic participants in particular) were included in these trials

- Model‐based studies create a composite of epidemiologic, clinical, and resource data from various empirical studies and databases, yet uncertainties in the data and model structures are unavoidable

- Areas of remaining uncertainty include the following

- The effect of persistent HPV infection and reactivation

- Clinical course after acquisition of new infections at older ages | Increasing life expectancies and potential cohort effects because of changes in lifetime sexual behaviors of US women over time are unknown

When to Consider More Frequent Testing

- The new ACS guidelines recommend HPV only testing every 5 years, however, these guidelines assume this patient is not immunocompromised or is not at otherwise medically higher risk for persistent HPV infection

- Patients who are at higher risk and should be screened more frequently

- Immunocompromised: HIV | History of solid organ or stem cell transplant | DES exposure | Other conditions associated with decreased immune response

- Medical history: Previous CIN2, CIN3, or AIS | Extend screening past age 65

- Are there factors that may lead to patient being less likely to adhere to screening at a date later than when she is in the office?

- Social factors

- Health insurance insecurity

- Transportation barriers

- Trauma with pelvic examinations

- Is this patient symptomatic?

- Postcoital bleeding is a typical early sign of cervical cancer | A mass on the cervix requires a biopsy

- Interval cervical cancer screening may be indicated for patients with persistent vaginal discharge, pain, etc.

- Does this patient have a new partner? Does her partner have a new partner?

- This may especially impact discontinuation of screening in older patients

Disparities

- Disparities have decreased but continue to exist in incidence and mortality from cervical cancer based upon geographic location, rural/urban residence and for racial/ethnic minorities (Fleming et al. PLoS One, 2014; Temkin et al. Gynecologic Oncology, 2018)

- The contributors to these inequities include barriers such as access to follow-up and treatment

- Provider bias contribute to inequities | Be an upstander and find ways to help patients overcome structural inequities that may impact care (Temkin et al. Gynecologic Oncology, 2018)

Cervical Cancer Screening for Women <30 years

- While ACOG/ASSCP/UPSTF recommend starting screening at age 21, ACS recommends beginning screening at age 25

- Substantially higher HPV positivity rates have been demonstrated leading to higher colposcopy rates than with cytology alone or co-testing (Ronco et al. Lancet, 2014)

- In the prospective US screening study evaluating the performance of primary HPV screening in women aged ≥25 years, however, HPV testing was significantly more sensitive for the detection of CIN3+ than cytology alone (Wright et al. Gynecologic Oncology, 2015)

- Both HPV16/HPV18 positivity and cytologic abnormalities were highest in women aged 25 to 29 years, and more than one‐half of the women in this age group who had CIN2+ (or CIN3+) identified on colposcopy had a negative cytology result

- In light of the increased detection of abnormalities in this age group, adherence to conservative management guidelines is recommended

Cervical Cancer Screening for Women >65 years

- The evidence from randomized trials for screening after age 65 is limited

- Most trials included women up to age 65, not older

- Limited data for screening older patients who have a new partner

- Guidelines generally recommend to stop screening average-risk women >65 for cervical cancer no history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2/3 or cancer and documented adequate negative prior screening

- However, because approximately 20% of new cases of cervical cancer are diagnosed in women ≥65 years of age, attention to patients in whom screening should continue is extremely important and include the following

- Patient without adequate prior negative screening defined as 2 consecutive negative HPV tests, or 2 consecutive negative co-tests, or 3 consecutive negative cytology tests within the past 10 years | Underscreening is common among patients over age 50 as the need for gynecologic care is often decreased

- Patients who are currently under surveillance for abnormal screening results

- Patients who are immunosuppressed

- Cervical cancer screening may be discontinued in individuals of any age with limited life expectancy

Vaccination

- Best public health strategy remains prevention associated with a substantially reduced risk of invasive cervical cancer at the population level

- HPV vaccine has been available since 2006 (Schiller et al. Vaccine, 2012)

- Vaccines if administered prior to the acquisition of HPV infection are highly effective at cancer prevention

- Wide variation across the US, with only about 50 percent of adolescents ages 13 to 17 up to date with the recommended regimen(Elam-Evans et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2020)

- Vaccination rates in your community may impact population prevalence of HPV infection which will change the positive and negative predictive value of cytology or HPV testing

- Recent attenuation of declines in incidence, an increase in diagnoses of metastatic disease and growing percentages of adenocarcinomas underscore the importance of continued efforts to further reduce the burden of cervical cancer in the U.S (Islami et al. Preventative Medicine, 2019)

Reduce Disparities in Gynecological Care

Women’s Health professionals have posted a petition as a call to action to (1) maintain the current ACOG cervical cancer screening guidelines (2) reduce disparities in gynecologic care and (3) ensure patient choice and individualizion of care. To learn more about the petition, click the button below

REFERENCES:

Cancer statistics, 2020 (Siegal et al. A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 2020)

Screening for Cervical Cancer in Rural India (Sankaranarayanan et al. NEJM, 2009)

Commercial Support

This educational activity is supported by Hologic

Faculty Disclosures

Dr. Temkin reports that she is an advisor for Tesaro/GSK and Clovis for which she has received honoraria

Related Curbside Consult Topics

Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines – Key Points for Shared Decision Making with Your Patients

Related ObG Project Topics

Screening for Cervical Cancer in the Woman at Average Risk

This site does not provide medical advice

The contents of the Site, such as text, graphics, images, information obtained from ObGConnect’s licensors, and other material contained on the Site (“Content”) are for informational purposes only. The Content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on the Site!

If you think you may have a medical emergency, call your doctor or 911 immediately. ObGConnect does not recommend or endorse any specific tests, physicians, products, procedures, opinions, or other information that may be mentioned on the Site. Reliance on any information provided by ObGConnect, ObGConnect employees, others appearing on the Site at the invitation of ObGConnect, or other visitors to the Site is solely at your own risk.